2015 NBA Trade Deadline, Pt. 1: Everything Involving Minnesota

Would you rather have a lottery-protected future first round pick or the greatest player in franchise history?

The NBA Trade Deadline was on February 19, 2015. We’ll discuss the 2015 Trade Deadline with either three or four (probably four) themed articles, each focusing on trades involving a particular team or topic. Our first part will look at the three trades made by the Minnesota Timberwolves.

The 2014-15 season was a bad one for the Minnesota Timberwolves. After nearly crawling to competitiveness the year prior, Kevin Love had been traded to Cleveland before the season and the competitiveness clock was reset. Andrew Wiggins took the 17th-most shots in the league, and they were going in often enough for him to win Rookie of the Year. That was about it in terms of highlights.

The team would finish a league-worst 16-66; the only team in the NBA to win less than 20% of its games. They went on a 15-game losing streak between December 10 and January 13. Expected contributors like Kevin Martin, Nikola Pekovic, and recent first-round pick Ricky Rubio were battling injuries that would keep them out for the majority of the season. The poor results would earn them a first-overall pick in the 2015 Draft, and the selection of Karl-Anthony Towns resulted in back-to-back seasons where Timberwolves fans got to cheer on the Rookie of the Year.

In part, we’re breaking out the Timberwolves into their own section of 2015 Trade Deadline coverage in order to study the moves a team can make at the deadline when they’re firmly out of contention. In part, we’re breaking it out because they were involved in the only two February trades that preceded the deadline, so it’s convenient to have them at the front. The weighting of these two measures is a confidential trade secret.

February 10, 2015

Minnesota Timberwolves receive: Adreian Payne

Atlanta Hawks receive: 2018 1st-round pick (#19, Kevin Huerter selected)

If you’re reading this, you’re either subscribed to a newsletter about trades or you’ve chosen to click on a post from a trade-themed newsletter. As an educated reader, you might have an inkling about the simple approach that a bad team can take as they approach a trade deadline – any talented (or expensive) veterans should be traded elsewhere in exchange for draft picks or young players with potential to improve (and cheaper contracts). The team gets worse in the present-day (increasing the odds of a favorable draft pick) but picks up pieces that may help in future seasons. We’ll call this the “Standard Tank Model.”

The Standard Tank Model is pretty hard to screw up, but its viability rests on some particular assumptions. The biggest assumption is that a team has “talented veterans” to begin with, and there’s an equally important corollary that other teams want to give you something in exchange for those talented veterans. The Timberwolves were unable to clear the two hurdles simultaneously. Kevin Martin and Nikola Pekovic might have been appealing for contenders to add to their rotation, but had missed substantial time with injuries and recently signed contracts that guaranteed them substantial salaries in future years. Convincing a team to trade assets for these players becomes much more challenging if they’re affecting future roster flexibility. All of the same conditions were true of Ricky Rubio, who was still a potential-filled fan-favorite and would’ve caused riots if he were actually traded at age 24.

This increased the degree of difficulty as the trade deadline approached. What could the Minnesota Timberwolves do to build for the future if nobody was interested in buying their present?

Apparently, they could trade away a future first-round pick. Not the answer I was expecting, and not one that makes any sense on its face! If we’ve learned anything from discussing the Philadelphia 76ers (which we’ll return to in our next post), it’s that rebuilding NBA teams want to accumulate as many future first-round picks as they can. Is Minnesota just terrible at making basketball decisions?

The evidence would suggest yes, they are, but that’s not the point — this is actually a pretty clever subversion of what we’re used to seeing. The Wolves were acquiring Adreian Payne, a power forward from Michigan State who was drafted 15th overall after a four-year college career. Payne had hype on his draft night, but showed up to an absolutely loaded Atlanta Hawks team that sent four of its starters to the All-Star Game. It would be a challenge for a rookie to get playing time under the best of circumstances, and missing the start of the season with plantar fasciitis ensured that Payne would be working in pretty suboptimal circumstances. Once healthy, the Hawks had coalesced into a world-beating rotation without him and Payne spent most of his time in the D-League, totalling just 19 minutes in 3 NBA games so far.

Just because a rookie couldn’t get playing time on a team in the throes of competitiveness didn’t mean that he couldn’t play in the NBA, and acquiring young players with room to break out was precisely the result the Standard Tank Model called for. Minnesota was willing to part with a future first-round pick for a couple of rational reasons. The most obvious is timing; beyond the discount value of present-day vs. future draft picks, the Wolves were planning to build a roster around 2014 first overall pick Andrew Wiggins, fellow 2014 first-round pick Zach LaVine and whoever they selected with their 2015 lottery pick (they also had the first overall pick from 2013 (Anthony Bennett) kicking around, but this was already uninspiring). A first-rounder from 2014 would fit the growth trajectory of this anticipated core better than a similarly-talented player drafted three years later. The other justification is pick value. Minnesota parted with a nominal 2017 first-round pick, but it carried lottery protections through 2020. Since the lottery covers the first 14 picks of the NBA draft, the Wolves would be acquiring that year’s 15th overall pick in exchange for a future pick that was guaranteed to be no better than 15th (and hopefully much worse).

Some Wolves fans appreciated this novel structure and noted that this move gave the Wolves six first-round picks from the last two years, all of whom except the already-effective Gorgui Dieng were taken in the top 15 picks. Others cast judgment on the Hawks for giving up on a recent first-round pick so quickly without providing a real opportunity for Payne to establish himself at the NBA level. But given the goodwill that the Timberwolves had burned by making bad moves for basically their entire existence, the most common sentiment was skepticism that Payne would have the type of impact that merited parting with the currency of a first-round pick.

Well, about one year later, a report indicated that Minnesota was looking to trade away a few players from its roster, including Payne. The top comment on Reddit was an all-caps “TAKE PAYNE PLEASE TAKE PAYNE SOMEBODY,” indicating that this trade had not gone especially well. The Timberwolves had given Payne copious playing time for the remainder of the 2015 season and learned beyond a shadow of a doubt that he was not qualified to play NBA basketball. Maybe there actually was still a shadow of a doubt, since Minnesota did pick up the third-year option on Payne’s contract to guarantee his salary through 2017, but the decision to give him a third year quickly aged poorly. Of the 475 players who attempted an NBA shot in the 2015-16 season, Payne’s eFG% of .397 ranked 436th. Only four of the guys below him in the rankings had more field goal attempts. With the burn from touching the stove still fresh on their hand, the Wolves declined to pick up Payne’s fourth-year option and let him hit free agency in 2017. He signed a two-way contract with the Magic and played five more NBA games. Payne only played 91 seconds in his final game, but managed to record a steal.

With no help from Adreian Payne, the Wolves remained in the draft lottery for the 2016-17 season, but finally put together a winning season once he had left the team. Six months after Adreian Payne played his final NBA game and three months after Minnesota hosted its first NBA playoff game in over a decade, the Hawks received Minnesota’s 19th overall pick in the 2018 NBA draft and used it to select Kevin Huerter. It can sometimes be complicated to discuss the racial dynamics and stereotyping involved with player evaluation, especially in basketball, but sometimes there’s a red-haired white guy from Albany named “Kevin Huerter” being drafted by the Atlanta Hawks and things are over-the-top enough to avoid any need for nuanced discussion. Huerter and fellow first-round pick Trae Young quickly formed a dynamic backcourt in Atlanta as the team built towards its competitive window. Things came together in 2021, when Huerter played a key role on a Hawks team that advanced to the Eastern Conference Finals and followed this success by signing a four-year, $65 million contract extension.

This trade was a neat idea on paper that played out disastrously for Minnesota. Payne was a higher draft selection than Huerter, but Huerter turned out to be the much better player. Of course, the Hawks traded Huerter to Sacramento less than a year after he signed his extension, receiving two players who are no longer with the team and a first-round pick that has yet to convey (Atlanta will receive the Kings’ pick this year unless it is within the top 12). Huerter went to Chicago at this year’s trade deadline as part of a much larger move that will contribute to the avalanche of blockbuster content we’ll have in February of 2035.

Adreian Payne’s post-NBA basketball career took him to Greece, China, France, Turkey, and Lithuania. In May of 2022, Payne’s girlfriend received a call from one of her friends letting her know that she was involved with a domestic dispute with her boyfriend, Lawrence Dority. Payne and his girlfriend drove to Dority’s house, where Dority approached their car and exchanged words before going into his house and returning with a gun that he used to shoot and kill the 31-year-old Payne. Dority was arrested on charges of first-degree murder and pleaded not guilty, alleging that he was threatened by Payne and acted in self-defense. Dority is still awaiting trial, with a status hearing scheduled for February 28, but the defense motion to declare Dority immune from prosecution under Florida’s “stand your ground” law was denied at the end of last year. There seems to be little evidence that would support his self-defense claim.

Minnesota Timberwolves receive: Gary Neal, 2019 Miami 2nd-round pick (#43, Jaylen Nowell selected)

Charlotte Hornets receive: Troy Daniels, Mo Williams, cash considerations

We already wrote about the trades that sent Gary Neal and this draft pick (eventually used on Jaylen Nowell) to Charlotte. Neither had done much to positively distinguish himself with Hornets — Neal’s shooting numbers fell off a cliff, while Nowell was still a high school student several years away from being drafted. I think it’s best for all of us if discussion of the Charlotte Hornets is limited to essential facts, allowing us to return to the Minnesota Timberwolves. Not exactly more inspiring fare, but at least on-topic.

There’s an NBA trope of the “looter in a riot” that was apparently coined by TNT’s Kenny Smith. The theory of the analogy is that in the smoldering chaos of a bottom-tier NBA team, players can end up posting statistics that overstate their on-court abilities. The player ends with an unreasonably high number of points just as the looter in a riot ends up with an unreasonably high amount of Best Buy merchandise. After all, NBA teams don’t lose games 100-0. Even a terrible offensive performance still results in several dozen points that need to be distributed among five starters and a few bench players. This is especially pronounced for a team like the 2014-15 Wolves, whose offensive performance was merely bad (97.8 points per game, 23rd in the NBA) in contrast to their laughable defensive performance (opponents scored 106.5 points per game, last in the NBA by more than a point over the 29th-place Lakers). The cops are not going to try very hard to stop your looting if you’re letting them take it all back with interest.

Plenty of Wolves were able to benefit from a lack of surrounding talent and team expectations. The most obvious was Rookie of the Year Andrew Wiggins, who got to play 2,969 minutes (no rookie since then has cleared 2,800). But there was also Corey Brewer, a career bench scorer who was only given the opportunity to start while he played in Minnesota. After starting his career with the Wolves in 2007, Brewer returned in 2013-14, dropped 51 points in a game at the end of the season, and then got traded to Houston (for Troy Daniels, in part) in a December trade that I didn’t write about because it was consumed by A.J. Preller’s ascent to the trade throne. Even though he left the team after just 24 games and even though his 51-point game was in the preceding season, Brewer was 11th in total points scored for the 2014-15 Wolves.

Mo Williams was similarly situated. Williams was a 2nd-round pick in 2003 who established himself as a solid starter with the Milwaukee Bucks and then made his reputation in Cleveland as the star of the much-derided “supporting cast” whose lack of talent induced LeBron James to take his talents to South Beach. In the aftermath, Williams was given the impossible task of leading the team after LeBron’s departure, then mercifully relieved from duty when he was traded to the Clippers at the deadline.

This marked the arrival of a phase where Williams was either a starting point guard on a losing team or an overqualified backup guard on winning teams. Williams moved to the bench in his second season in Los Angeles, which coincided with the Clippers’ first playoff series victory in six years. He was traded to the Jazz that summer and started every game he played in as the team missed the playoffs, then signed with Portland, returned to the bench, and won a playoff series. This final playoff series added intrigue, as it included Williams starting an altercation with Troy Daniels of the Rockets after Game 4. Williams explained to reporters that “he knows what he did,” but then explained that this was a psychological tactic to get in the rookie’s head after a hot shooting performance. We’ll circle back on this later.

Entering his 12th NBA season, Williams signed a $3.75 million contract with Minnesota in free agency and took an increasingly large role in the offense as expected starters fell to injury. For instance, in a late November matchup of the 3-10 Wolves versus the 3-12 Lakers, Williams scored 25 points and posted 11 assists to lead Minnesota to a one-point victory. The next game, Williams played an even 40 minutes against Portland, dishing 11 more assists and scoring 21 points of his own. The Wolves lost by 14. For contrast, the 25/11 performance came on a day where Chris Paul had 10/7 and the 21/11 came on a day where Steph Curry had 16/10. Mo Williams was not better than either of these players, but he was granted an opportunity to create evidence to the contrary given that his team more closely resembled a riot.

The most memorable example came on a cold Tuesday night in Indianapolis, where the 5-31 Timberwolves squared off with the 15-24 Pacers. The Pacers were having a dreadful season after a couple of years doing battle at the top of the Eastern Conference, but their basketball-crazed city still sold out the stadium for 14 of their 41 home games. This January 13 matchup with the Timberwolves was not one of them. Attendance was announced at 16,781, but those that showed up were not especially loud. Minnesota hadn’t won a game in more than a month. This would be a great game to take your family to as long as your kids were too young to actually want to watch basketball.

The night started as just another strong game for Williams. In the first quarter, he played an all-around facilitator role, compiling three assists and three rebounds. He heaved and missed a shot at the buzzer to bring his shooting down to just six points scored on seven attempts. The shooting ticked up in the second quarter, and when the first half ended, he was 7-for-12 with 15 points. Good, but not particularly notable on either volume or efficiency. The Wolves trailed 52-46. Three minutes elapsed in the third quarter before Williams was able to make his first shot of the second half, but the next three went in as it became increasingly clear that Williams was looking to finish possessions on his own. As he scored his 23rd point, the Pacers broadcasters observed “it’s all about Mo Williams now.”

For the first 23 points, Williams’s performance had been a masterclass in the sort of basketball that’s become outdated in the last decade – shots from every conceivable part of the court outside the paint as long as they were two-pointers. The dynamic changes with about two minutes left in the third quarter. Williams passes to Andrew Wiggins, who feeds him the ball back as he runs to the corner to drain a three-pointer. If Williams didn’t already realize he was having a night, this clues him in. One possession later, Williams sprints to the top of the arc and fires a 26-foot shot with 17 seconds left on the shot clock. The Pacers commentator grunts in astonishment as he realizes that ball is going in. And on the final possession of the quarter, Williams brings it back to the classics as he dribbles into traffic before launching a midrange shot that two defenders contest. It banks in cleanly, eliciting an “ooh” from the Pacers commentator and bringing Williams to 31 points on the evening. This output has not changed the game state; Minnesota continues to trail by six.

When sports fans talk about coaches having a “feel for the game” and express their disgust with “sports being played on a spreadsheet,” they’re implicitly defending a situation like this. Over the large sample of his career, Mo Williams is a 43% shooter, a rate that drops to 40% if you limit it to his season in Minnesota. While that sample is surely more predictive of his performance on a long-term basis, it would be insane to rely on the more reliable number over the performance we’ve just witnessed over the last three quarters. Over the large sample of the season, your team is 5-30 and over the sample of this game, your team is losing by six. The shots Williams made to end the third quarter are more than enough evidence of divine intervention for you to rely upon in your current context. The Mo Williams on your court today is a deified form of the man you thought you knew, and the correct course of action is to sing Hallelujah and put your faith in Him.

With 4:50 left in the 4th quarter, Andrew Wiggins grabbed an offensive rebound and dunked it to tie the game at 90. The Wolves had 69 points when the quarter started and the 19 points that brought them up to a score of 88 were either scored or assisted by Williams, who took advantage of open teammates as the Pacers started double-covering him. A previously quiet crowd in Indianapolis started to roar with disgust with each shot Williams made, particularly after he made a one-footed fadeaway three-pointer to tie the game at 88 and bring his scoring total up to 45. A loud “defense” chant emerged with about 90 seconds to play and Minnesota leading by three, but after Williams made another circus three it was silenced and replaced by three increasingly incredulous “no!”s from the Pacers commentator. He made four free throws in the final minute of the game to bring his total to 52 points, the highest total in Minnesota Timberwolves history and the most an opposing player had scored since the arena now known as Gainbridge Fieldhouse was built in 1999. Three players have since exceeded that total (chronologically and ascending: Russell Westbrook, Giannis Antetokounmpo, and Devin Booker), but weirdly, the Pacers won all three of those games, meaning Williams can still boast the most dominant scoring performance by a visitor who left with a victory.

When Mo Williams was traded to Charlotte a month later, this performance was fresh enough in everyone’s mind for Charlotte to quickly emerge as the reputational victors. Humor was found in the fact that after sparring as a Trail Blazer and Rocket, Williams and Troy Daniels were now going from the Wolves to the Hornets in tandem. I’m not sure why this was funnier on the occasion of this trade than it was when they became teammates two months ago, but I don’t blame casual observers if they weren’t tuning in to 2014-15 Minnesota games. As we briefly alluded to in last year’s Gary Neal discussion, most of the excitement from a Charlotte perspective was directed towards no longer having Gary Neal on the team. For a Hornets team that could still see themselves in the playoffs, acquiring Daniels and reuniting Williams with longtime friend Al Jefferson could provide a spark down the stretch.

There was basically one good week. Between March 1 and March 8, the Hornets went 5-0, with Williams averaging 20.2 points and 10.8 assists in that span. He was named Eastern Conference Player of the Week after winning Western Conference Player of the Week earlier that season, becoming the first player to win the award in both conferences during the same season. Besides those five games, the team went 6-19 during the Mo Williams era to finish the season 33-49. He signed a two-year contract with Cleveland that summer, lost playing time over the course of the season as he developed a knee injury, and announced his retirement after the first year.

You might not see a distinction between “Mo Williams announced his retirement,” and “Mo Williams retired,” but there is one, and it became relevant as the season tolled on. In most jobs, they will not pay you your $2.2 million salary if you’ve announced your retirement and no longer come to work. In the NBA, that makes you a valuable asset.

Even after his playing career ended, contractual Mo Williams made a valuable contribution to the ecosystem of the NBA. First, the Cavaliers used him to match salaries in a trade that brought Kyle Korver to town. Then, Atlanta traded him to Denver to create a trade exception, then his contract was claimed by Philadelphia and Denver once again in order to bring both of these team payrolls up to the NBA’s salary floor by leveraging a CBA loophole that was going away that offseason. This is like watching the wolves, vultures, worms, and microbes all take their turns feasting on the gradually shrinking carcass of a deer. Williams started coaching at the collegiate level in 2018 and is currently head coach at Jackson State after an earlier stint at Alabama State.

Troy Daniels had a smaller role in Charlotte, but a longer tenure, sticking around for one more season before going to Memphis in a sign-and-trade. His final NBA season was 2019-20 and started in Los Angeles, which eventually resulted in Daniels receiving a championship ring. But he was waived by the Lakers on March 1 and signed by the Nuggets on March 5. He got his first action in Denver when he played 44 seconds on March 9, and then the world shut down due to a pandemic. A few months later, Daniels and the rest of his teammates for the past 44 seconds showed up to Disney World to play in the NBA Bubble. The final 11 games of his NBA career took place in that setting, with his final game coming in Game 2 of the Western Conference Finals (played on September 18). Daniels took three shots and scored eight points to end things on a high note, even though his team lost to the team whose eventual championship would result in his receipt of a championship ring.

Gary Neal only played in eleven games for Minnesota. They won the first two and lost eight of the final nine. The final win was the only game where Neal was clearly “good” based on the box score, and he didn’t play at all after March 22. When we discussed Neal last year, he was head coach at Calvert Hall College High School and I was trying to figure out his record in his second and third season. I could account for a 39-47 career record to that point, but acknowledged that tally to be inconclusive. About a month after that post was published, Neal resigned as head coach with a reported career record of 45-59, including a 5-37 record in Baltimore Catholic League regular season play that implies it was substantially worse than I could’ve comprehended.

The quiet irony of this trade, from a Standard Tank Model perspective, is that the only future asset that the Wolves acquired for their franchise leader in single-game scoring was a 2nd-round pick from the far off year of 2019. The low implied value of a future #43 pick was mitigated by the fact that Nowell was quite an effective depth piece for Minnesota on his rookie contract, growing into a role where he played 19 minutes per game in his final season with the team. This didn’t translate into long-term career stability; Nowell has played more games in the G-League than in the NBA in the two seasons since leaving the Wolves. He played eight games for New Orleans this season before he was waived and signed a 10-day contract with Washington on February 8. He didn’t play in either of the two games they had scheduled before the All-Star Break, and on the 18th they signed a different guy to a 10-day contract, thereby ending Nowell’s Wizards era before it began. Neither he nor the draft pick used to select him were traded again after this deal, so we may never hear from him again.

February 19, 2015 (Deadline Day)

Minnesota Timberwolves receive: Kevin Garnett

Brooklyn Nets receive: Thaddeus Young

The final category of things to do at the trade deadline is to make your fans happy. This is arguably the goal of every trade in the long-run, with executives assuming that their preferred transaction will increase the number of games the team can win (whether the focus is short-term or long-term). As a general macro rule, fans are fickle, and your team needs to consistently win games to keep them engaged.

Sometimes you can take a shortcut.

Haywood v. National Basketball Association, 401 U.S. 1204 (1971) was a Supreme Court case that shot down the NBA’s minimum age requirement. Prior to Haywood, players were prohibited from signing a contract with an NBA team until four years after their high school graduation. Practically speaking, this meant that players needed to spend four years playing college basketball before being drafted. In 1975, Darryl Dawkins and Bill Willoughby took advantage of the new landscape to enter the NBA Draft immediately from high school. It didn’t seem like either made the right decision, and Willoughby later spoke to incoming NBA players about the regrets he had over not attending college. For twenty years, the two men stood alone as something between a historical oddity and a cautionary tale.

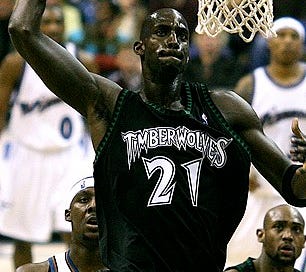

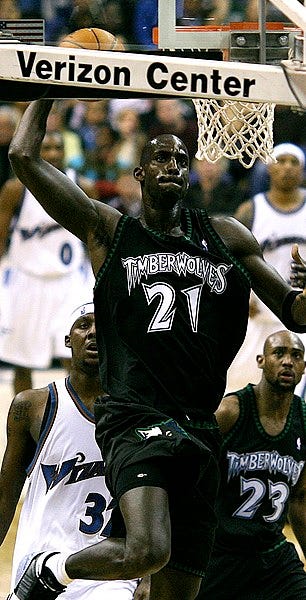

In 1995, Kevin Garnett was the best high school basketball player in the country. After an MVP performance in the McDonald’s All-American Game, Garnett became the first high schooler to declare for the NBA draft in 20 years. The Timberwolves had completed six seasons of play as an NBA franchise and had failed to reach the 30-win mark in any of them; they were willing to take a risk on an unseasoned Garnett with their fifth overall pick. His rookie season was more “respectable” than “dominant,” and his 6th-place finish in Rookie of the Year voting seemed to lag behind his 5th overall draft selection, but to be doing this as one of the youngest players in NBA history portended superstardom in the near future.

It didn’t take long, especially when the Wolves paired Garnett with Stephon Marbury. In his second season, Garnett made his first All-Star team and led Minnesota to a 40-42 record. That may not look impressive, but it was by far the best Timberwolves season ever and resulted in the franchise’s first playoff appearance. Before the 1997-98 season, Minnesota signed Garnett to a wholly unprecedented contract extension worth $126 million over six years. The amount “$126 million” probably looks pretty big no matter what year you’re reading this in, but was an absurdity in 1997. For context, Glen Taylor had purchased the franchise for $88.5 million two years before agreeing to these terms with Garnett. Based on the reported $1.5 billion purchase price in the 2021 sale of the Wolves, this would be something like giving Anthony Edwards a $2.2 billion contract extension last year. Ridiculous contract. It immediately and basically directly led to a lockout that shortened the 1998-99 season to 50 games.

This is a good opportunity to note that KG’s quick success in the NBA ushered in a sea change among high school basketball players. After 20 years without a “prep-to-pro” player in the NBA, two more high school players (Kobe Bryant and Jermaine O’Neal) entered the NBA Draft in 1996. Every successive season had at least one first-round pick who was drafted straight from high school until the ratification of the 2005 CBA, which reinstated a restriction on drafting players until they were one year removed from high school graduation. After twenty years where no player was willing to buck the expectation of attending college, 38 players followed Kevin Garnett’s lead in the 10 years where it was allowed after his entry to the draft.

Garnett lived up to his end of the megadeal, improving to become one of the league’s best players over the contract’s six-year term. But he found himself stymied by an organization that couldn’t stop tripping on its own feet. Marbury was traded to New Jersey during the 1999 season following considerable acrimony that reportedly had roots in resentment over the fact that he’d never make as much as Garnett under the new CBA. That same year, the team attempted to circumvent the salary cap by signing Joe Smith to a very cheap deal for a few seasons and promising to make it up with an $86 million long-term contract on the backend. The scheme was discovered and brutally punished by the NBA, with Minnesota made to forfeit its first-round pick in every season from 2001 through 2005 (they eventually got two of them back). These hindrances combined with Garnett’s prodigious talent resulted in a strange alchemy of a team that could consistently win about 50 games and make the playoffs, followed by an unceremonious first-round exit.

In 2003-04, everything came together (at least, on the Timberwolves grading curve). Garnett posted a new high in scoring with 24.2 points per game and led the league in rebounding as Minnesota went 58-24. This was (and still is) a franchise record for wins in a single season, and Kevin Garnett was named MVP for the first time in his career. But more impressively, the Wolves finally advanced in the playoffs, beating Denver in the first round and Sacramento in the second to set up a Western Conference Finals matchup with the Lakers. The dream run ended when Sam Cassell, the team’s second-best player and starting point guard, suffered a back injury. The KG show was not enough to hold off the Lakers and the Wolves lost in six games.

If you’re not sufficiently familiar with Kevin Garnett, it’s important to clarify that an essential part of his charm is psychopathy. Garnett played (and did basically everything else) with the type of intensity that helps clarify how some talents become all-time greats while others have forgettable careers. He showed up to a franchise that had staggered in mediocrity for its entire history, then elevated them to a perennial 50-win team through unparalleled force of will. KG was the “franchise player” for the Minnesota Timberwolves to a degree that might not have a parallel in any other 21st century sport. Even if Garnett weren’t quite so excellent on the court, he would’ve been beloved in any city that got to spend this much time cheering for him.

But in the seasons following the MVP year, the Timberwolves fell back to their old standards. Continued greatness from Garnett was not sufficient to keep Minnesota above .500, and as the one-time wunderkind reached his 30th birthday with just one year left on his contract, it became increasingly nonsensical to keep him on this roster. Over the summer of 2007, the Wolves began exploring Kevin Garnett trades. In June, Garnett’s agent publicly stated “the Boston trade isn’t happening” because “that’s not a destination we’re interested in pursuing.” KG’s preference was either to play in Phoenix or to team up with Kobe Bryant in Los Angeles. Apparently Kobe didn’t return his calls, and after moves to these destinations failed to materialize, Garnett had a change-of-heart about Boston. On July 31, the Wolves traded the best player in franchise history to the Celtics in exchange for seven players, which was the greatest number of guys exchanged for a single guy in league history.

The two roads diverged from there. Garnett immediately won his first Defensive Player of the Year award and NBA Championship upon arrival in Boston, picked up a knee injury that caused inconvenience for the rest of his playing career, and was later sent to Brooklyn in one of the most legendary trades in league history. The Timberwolves returned to the abyss that they made their home in their non-KG years. By February of 2015, it was clear that the Nets’ experiment had failed. Garnett’s contract was set to expire at the end of the season. He had a full no-trade clause, but there was at least one city (or set of twin cities) where he’d happily return.

Thaddeus Young had arrived in Minnesota as part of the Kevin Love swap and as a 26-year-old starter with an expiring contract, was ostensibly a deadline trade piece. Was it reasonable to trade Thaddeus Young just to acquire the nostalgia of Kevin Garnett? No. Were Minnesota fans going to let that objectivity color their opinion on this trade? Also no. The Nets were able to re-sign Young to a four-year contract, then traded him to Indiana one year later. As we wrote in August, he gets traded six times in his career, and this is only the second, so we’ll be coming back to him frequently. He was looking for an NBA contract when we last checked in and still has not signed one, but his wife posted a video of him shooting on Twitter in January, and when someone replied to it with “let the man Rest he’s put in his work for years He deserves a break” she responded with “Thad hasn’t officially retired!”. The quest continues.

The Timberwolves basically got what they wanted from this trade. On-court, that amounted to very little. Garnett played in five games down the stretch in 2015 (all home games in Minnesota), re-signed that summer, and played 38 more games in the 2015-16 season before his knee injury shut down his season. Minnesota went 14-29 in the games KG played in during his second stint with the team. All of that is really besides the point. When Garnett became the fifth NBA player to reach 50,000 career minutes, he did so in a Timberwolves uniform. When he scored his 26,000th career point, he did so in a Timberwolves uniform. When he became the NBA’s all-time leader in defensive rebounds, he did so in a Timberwolves uniform. And when he announced his retirement after 21 seasons, he did so as the best player in the history of his franchise.

Commemorating trades is fun because they’re either a moment of departure or arrival for one of the limited number of players that have suited up for a franchise. There have only been 302 Minnesota Timberwolves, ever, and only 160 have stuck around for at least 50 games. Most of the guys we’ve talked about today don’t hit that threshold. Thaddeus Young played 48, Mo Williams was there for 41, Troy Daniels got into 19, and Gary Neal was only around for 11. Kevin Garnett had 927 career games with the team and then played 43 more after returning. I don’t know how the other four guys would rank in an all-time comprehensive list of The 302 Most Important Timberwolves, but they’d definitely be somewhere in the bottom 301. It’s hard to go wrong when you can acquire the most important player in the history of your franchise via trade, even for an organization so skilled at getting it wrong.

For more on the post playing Kevin Garnett, check out the 2019 film Uncut Gems. For more on the Minnesota Timberwolves getting it wrong, subscribe to Trades Ten Years Later and stay tuned for at least the next ten years.